Gerelkhuu Ganbold – The Visual Narrator, by Amanda Sheppard

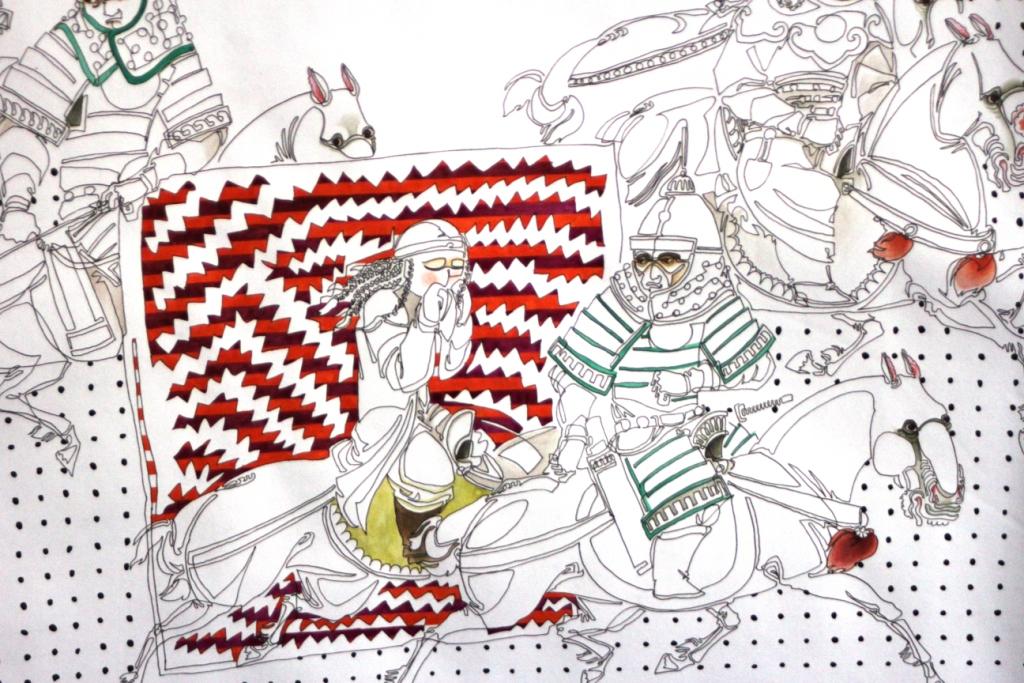

Aimless journey. Intruder of the past. Soldiers who don’t know themselves… These are the eponymous titles of Gerelkhuu Ganbold’s paintings. The Mongolian artist’s pieces exude a fierce yet alluring quality, emblematic of the country’s tumultuous, militarised history and the notion of an uncertain future. We speak about the fragility of urban life, the various ways to identify a home, and more…

A contemporary painter using the traditional Mongol Zurag technique, depicting folklore, war motifs and historic imagery in a modern and innovative way, Ganbold is one of the artists contributing to Ulan Bator’s growing reputation as a cultural capital. A home grown talent and former student of the University of Art & Culture, he has since exhibited his works internationally, in such places as Australia, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, and New Mexico.

But it is the city of Ulan Bator in which he creates, and where key influences on his painting can be identified. The city’s population has soared, with the sprawling Ger district continuing to grow as people seek warmer climes and the promise of a new life away from the steppe. The government have placed a ban on further migration for a year in an attempt to reduce air pollution in the capital, though whether such an implementation will be successful remains to be seen.

Migration is a vast ink piece – 12 panels detailing traditional motifs and war symbols with a select use of colour. But this is not a piece rooted in the past. “There are many traditional elements left in the past, because of changing lifestyles and society. But there are also traditional elements that continue to keep their meaning today; some of them dating back thousands of years. Some things never change, such as human’s inner conflict, the complex problems of communication, love, jealousy, war and its reasons. We are living in the 21st century and we still have problems that our ancestors had.”

When asked whether this piece project the way he himself perceives his home, Ganbold philosophises, “it depends what you call home. For me home is our universe. My art is influenced by people who are living and people who have passed in this world, and by every single movement of society.” On one thing, however, he remains firm. “I always try not to be influenced by art itself”. Not one to follow trends or to be shaped by growing movements, Ganbold’s paintings are uniquely personal, and highlight his experiences and relationships with both people and place.

Ganbold’s work brings him to experience new places, and to communicate with new cultures. I ask him what he notices first in a new city – “its people’s connections, their attitude, and how they keep their culture”, he tells me.

And of the people who travel far and wide to Mongolia? “I’m not sure about tourists and their expectations, but many international art experts have come to visit us, and they do find what they are looking for.” Ganbold is bold not only in the statements he professes aloud, but also with the ones made within his work –in the uncomfortable questions he dares to raise.

Wonder Magazine link to article

ON ART AND AESTTETICS interview with Baatarzorig Batjargal

ON ART AND AESTTETICS interview with Baatarzorig Batjargal