E-Flux: Five Heads (Tavan Tolgoi)—Art, Anthropology and Mongol Futurism

Artists: Nomin Bold and Baatarzorig Batjargal, Bumochir Dulam, Yuri Pattison, Hedwig Waters, Dolgor Ser Od & Marc Schmitz (with Nomadic Vitrine), Rebecca Empson, Deborah Tchoudjinoff, Lauren Bonilla, Tuguldur Yondonjamts, Rebekah Plueckhahn

“Five Heads (Tavan Tolgoi)” opens with video Gee, Ulaanbaatar, October 2017 (2018), an interview with the Mongolian rapper Big Gee filmed by artist and researcher Hermione Spriggs (who curated the exhibition) with Alice Armstrong and Curtis Tamm. Gee reflects on the complicated relationship between the Mongolian government, population, and the rapid economic and political changes in the country—themes which are further explored by the other works in the show. “In 2011, foreigners used to call Mongolia mine-golia,” Gee says. The country’s government told people they would get rich from mining. In fact, the selling of mining resources caused environmental degradation and starved citizens of any benefit. By 2015, the miners had relocated, leaving a polluted landscape and a country in debt.

“Five Heads (Tavan Tolgoi)” emerged from an ongoing, five-year research project led by anthropologist Rebecca Empson in the Department of Anthropology at University College London (UCL). As part of the research, five artists and artist collectives were paired with five anthropologists—all of whom are carrying out fieldwork in Mongolia on its volatile economy and vast mineral reserves—to conceptualize and critically engage with the possibilities of financial and political crisis. The Tavan Tolgoi that lends the exhibition its title is Mongolia’s most significant coalfield; the “five heads” are five mineral-rich mounds. A book published by Sternberg Press documents the exchange process between the artists and anthropologists in more detail, offering critical and theoretical essays on aesthetics of estrangement, geo-ontology, speculative post-capitalist futures, and alternative strategies for survival. Although not a prerequisite—the exhibition is rigorous and intriguing—viewers would need to read these essays to understand the full depth and range of the research involved in the UCL project, which is only obliquely touched upon in the art itself.

Tuguldur Yondonjamts’s digital print on mylar, 78-291, 875-953, 3006-3106 (Mirror Princess) (2018), which resembles an enlarged roll of analogue film, explores notions of mapping. The work was inspired by the artist’s collaboration with anthropologist Rebekah Plueckhahn, in which they walked throughout Zuun Ail, an area in Ulaanbaatar that is being swiftly redeveloped. Yondonjamts also has shares in the Tavan Tolgoi mine, demonstrating his involvement in repurposing the complicated economy latent within the mineral resources, and coal pigment is used in the print. Thinking about alternative modes of cartography, Yondonjamts explores three parts of a “Khan Kharangue,” a Mongolian poem and singing ritual whose title could be translated as “Darkest Dark,” transposed into the binary music of the morin khuur string instrument. Yuri Pattison’s pick, press, fang feng (the new economy) (2018) also takes an emblematic object of Mongolia as its starting point: the medicinal root Fang Feng. An LCD video monitor laid flat on the floor shows fuzzy footage of undergrowth and foliage with a pill press—frozen in motion, with crushed powder and scattered tablets spilling out—standing on its screen. Fang Feng is traded to China and sold internationally as a Western pharmaceutical product, one of many legal and illegal commodities being extracted from Mongolia to alleviate its debt.

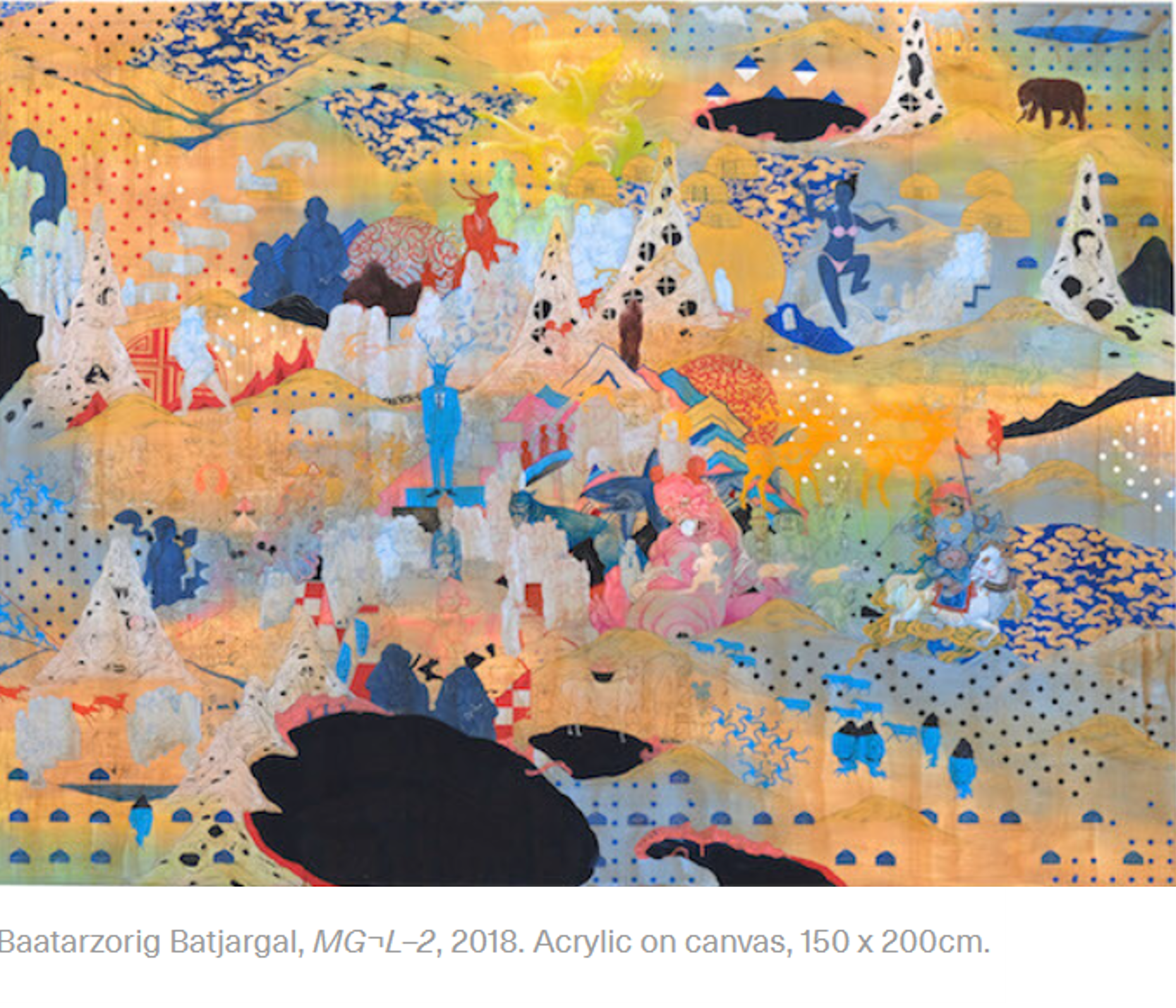

In his two lurid acrylic paintings—“MNG 1 & 2” (2018)—Baatarzorig Batjargal converges the hallmarks of “One Day in Mongolia” genre painting, which depicts scenes of nomadic life, with contemporary Western references. There is a cruel-looking Mickey Mouse and a ghoulish Uncle Sam alongside suited men with the heads of deer or reptiles. These figure are a response to Bumochir Dulam’s research into a ritualized “spiritual cleansing” of former Mongolian Prime Minister Chimediin Saikhanbileg after he signed a deal to deregulate international interests at the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine in 2015. The neoliberal economy is signified as a psychedelic landscape on the brink of conflict and collapse: the mountains are inhabited by dogs, while a surreal mix of hybrid beings and monstrous creatures war and flee.

Dolgor Ser-Od and Marc Schmitz’s assemblage North of the North Pole (in memory of Rasmussen) (2018) is housed in Andrew Gillespie’s roaming project Nomadic Vitrine (2016–ongoing), a display case that travels between venues, featuring different artists’ work each time. Ser-Od and Schmitz’s chosen found objects, which are displayed like museum specimens, include 24k plated copper, bronze, gold rocks, iodine, drawings, and various objects such as a cracked iPhone, a pair of boots, and two large calligraphic brushes. It’s a riff on colonial discovery (and extraction) that is also suggestive of a fantasy of elsewhere—north of the North Pole. The ideas of reciprocity and exchange integral to sharing across disciplines and borders, meanwhile, are encapsulated by Deborah Tchoudjinoff’s Baigala (2018). Comprising five VR headsets connected to saddle-like stools, the work immerses viewers in scenes of everyday life in western Mongolia, such as sitting drinking tea in a yurt. Regardless of how oblique the anthropological research can feel in relation to other works in the exhibition, Baigala transmits a direct line to a community of people who are often silenced or repressed by their country, allowing the images to speak for themselves, and encouraging viewers to observe, study, and imagine.